Settle in for some science and facts about soy and cancer. This guide will set you up with the truth about the role of soy foods for estrogen and testosterone, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and more.

If you’ve been diagnosed with cancer or know someone who has, you don’t need me to tell you it’s a scary, vulnerable time. There are so many unknowns and treatment options can feel overwhelming. Perhaps it’s no surprise many people turn to nutrition to help them through cancer treatment or recovery.

Food, and the nutrition found within, can do a lot to support good health. But on the flip side, the fear is that it can also have harmful effects. Such is the case with soy. So this post will break down some of the most common myths about soy and cancer to clear up the unfounded dangers of soy. I’ll share the facts instead, so you can make an informed choice about whether you want to eat soy foods or not.

If you haven’t already, read through my post “Is It Safe To Eat Tofu Every Day?” That’s where I tackle some of the most common myths about tofu and soy foods in general. Since this post focuses on soy and cancer, I kept it separate to help you find what you’re looking for.

Table of contents

Use the links above to jump ahead to any of the sections if you’re in a hurry. Otherwise, let’s cover the basics about soy and cancer starting with soy isoflavones.

I am a registered and licensed dietitian, but that does not mean I am your dietitian. The information shared and posted on this blog is simply meant to provide education and inspiration. It is not a substitute or replacement for medical advice, medical nutrition therapy, or individualized nutrition counseling. I will always recommend that you speak with your primary healthcare provider before making any changes to your diet or lifestyle.

Introduction to Soy Isoflavones

Our food culture is fixated on getting enough protein, which is partly why whole soy foods like tofu, tempeh, seitan, and edamame have gotten more popular. Plant-based diets and veganism are not a trend, they are here to stay! Plant-based protein gets a lot of attention, and rightly so.

But there are many other components of soy foods that are worth a closer look. And when it comes to soy and cancer in particular, we need to shift our focus to soy isoflavones.

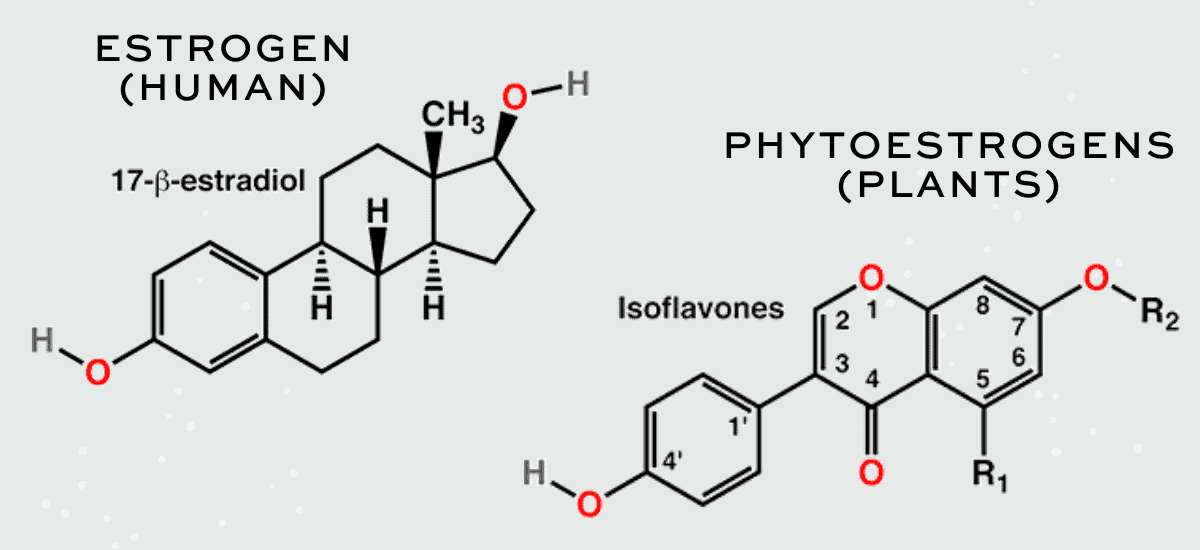

“What are isoflavones?” you might ask. Generally speaking, isoflavones mainly act as phytoestrogens (plant estrogens). They are naturally occurring. Soy has the highest concentration of phytoestrogens as isoflavones. But other types of phytoestrogens include lignins, resveratrol, found in grapes, cranberries, blueberries, cocoa and dark chocolate, and peanuts and pistachios. Plus flavonoids like quercetin, found in a variety of foods like grapes and berries, olive oil, and green tea.

Fun Fact: There are three unique isoflavones in soybeans: genistein, daidzein, and glycitein.

And, as you might know, the human body also produces its own form of estrogen. Estrogen plays various roles in the human body. But it’s mostly known for its important role as a sex hormone for reproductive health and development. Phytoestrogens have some important functions for plants and can be part of their defense mechanisms, especially against certain types of fungi. The hormone estrogen (in humans) and phytoestrogens (in plants) have a very similar chemical structure, yet they behave very differently. Keep reading to learn how.

Soy Isoflavones and Estrogen

In the human body, isoflavones can bind to estrogen receptors in cells just like the forms of estrogen our bodies make on their own. This was cause for concern for some people, who assumed that soy food consumption, and the resulting soy isoflavone intake, could fuel the growth of estrogen-specific breast cancer. Another fear was the eating lots of soy could lead to worse outcomes for women already diagnosed with breast cancer or in remission from breast cancer. The risk of cancer recurrence is never far from the minds of breast cancer survivors.

However, this is where we get to nerd out on some biochemistry and physiology. Because while estrogen binds to receptors ERɑ (estrogen receptor alpha) and ERβ (estrogen receptor beta), isoflavones only bind to and activate ERβ receptors. This is important to note because the two estrogen receptors have different tissue distributions.

- ERɑ is mainly present in breast tissue and mammary glands, as well as tissue in the ovaries, bones, prostate, male reproductive organs, liver, and adipose (fat) tissue

- ERβ is found in tissues of the prostate, bladder, ovaries, colon, and the immune system

- Both types of estrogen receptors are active in the cardiovascular and central nervous system

Here’s a key fact: soy isoflavones prefer ERβ. They are believed to have tissue-specific effects and are classified as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM). In other words, the type of plant estrogen you ingest from foods in your diet don’t have the same effects as human estrogen that your body makes on its own. Soy isoflavones may even act to inhibit cancer growth and suppress tumors.

Isoflavone Content in Soy Foods

When it comes to disease risk, it’s important to note how much of something can increase or decrease risk. After all, the saying is “the dose makes the poison.” Too much or too little water or oxygen, for instance, can be deadly even though both are essential for life.

The isoflavone content of soy foods can vary greatly. It can depend on the type of tofu or soy food, it’s preparation, and where and how the soybeans were grown. As a general rule, traditional soy foods like tofu have about 3.5 mg of isoflavones per gram of protein. Other, more modern types of soy foods like soy-based meat alternative, have 1-3 mg of isoflavones per gram of protein.

Another common piece of misinformation is that more highly processed soy foods, like soy protein isolate or TVP (textured vegetable protein made from soy) has a more concentrated amount of isoflavones. In fact, the opposite is true, as some isoflavones are lost during processing.

Here are some of the isoflavone contents for commonly eaten soy foods (from highest to lowest amount):

- 3 oz (85g) tempeh: 63 mg of isoflavones and 18 grams of protein

- 1/2 cup of shelled, cooked edamame: 34.6 mg of isoflavones and 9.9 grams of protein

- One cup of soy milk: 29.1 mg of isoflavones and 8.8 grams of protein

- 3 oz (85g) of tofu: 28 mg of isoflavones and 8 grams of protein

- Soy protein bar (45g): 11 mg isoflavones and 11 grams of protein

- One scoop of soy protein powder (23g): 20 mg of isoflavones and 20 grams of protein

Facts About Soy and Breast Cancer

Not only is it safe to eat soy, but soy can actually have a protective effect against breast cancer in some cases. The effects vary, with lots of factors at play. It depends on if you’re pre- or postmenopausal, how old you were when you started eating soy foods, how much you eat, and the type of breast cancer.

First, let’s look at what the data says about soy and breast cancer prevention.

Can eating soy prevent breast cancer?

The role of soy foods in breast cancer prevention is an extensively researched topic. In 2013, a meta-analysis was published that looked closely at 12 studies done in Asia. It found an association with a higher intake of soy foods and a 29% reduction in the risk of developing breast cancer. This review also indicated that the greatest opportunity for benefit comes from eating soy earlier in life. In other words, eating a variety of soy foods during childhood and adolescence may further reduce the risk of developing breast cancer.

We have historically seen this with the rates of breast cancer being much higher in the United States than in many Asian countries, where moderate soy consumption is more common. However, as many cultures become more westernized, we see that rates of breast cancer among Asian women are increasing. “Moderate intake” is two servings per day of whole soy foods like tofu, soy milk, or edamame.

The amount of dietary isoflavones from soy varies, with Asian populations consuming the highest amounts. For example, a 2006 analysis found it ranged from 10-15 mg/day in Hong Kong to 30-40 mg/day in Japan and Shanghai. Compare that to just 3 mg/day in Western populations. But even if American women suddenly started eating much more soy, they would not experience harmful effects.

The bottom line: eating soy at a young age can have a protective effect to reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. However, if you’re reading this now and didn’t grow up eating a variety of soy foods, it’s likely too late to reap these potential benefits. Instead, we can also look at the role of soy foods during or after cancer treatment.

Can I eat soy if I have breast cancer?

The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health compiled and consolidated data from prospective and observational studies from recent years. Here are some key findings:

- Women with breast cancer in North America who ate the highest amounts of soy isoflavones had a 21% lower risk of death compared with women with the lowest amounts.

- Data from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study showed women who ate the most soy had a 59% lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer compared with those who ate the lowest amounts of soy. However, this study also found no association for postmenopausal women with breast cancer.

- Among breast cancer survivors, the Life After Cancer Epidemiology Study concluded that “soy isoflavones eaten at levels comparable to those in Asian populations may reduce the risk of cancer recurrence in women receiving tamoxifen therapy and does not appear to interfere with tamoxifen efficacy.” But (this is important), the findings need to be confirmed by additional research.

You can find the rest of their findings HERE with many links to further reading.

At this point, there haven’t been any clinical trials looking into the role of soy foods and breast cancer recurrence specifically. However, if we focus on one marker of breast cancer risk (mammographic density) we see that isoflavone intake has no effect. Meaning, it doesn’t help prevent or reduce risk of breast cancer. But it’s not harmful and won’t increase your risk either.

Since 2012, the American Institute for Cancer Research and the American Cancer Society have said it’s safe to consume soy foods. Current research now shows that high doses of isoflavones do not have an effect on the growth of breast cancer.

At this point, it’s been over ten years since science has disputed these initial claims to show there are no dangers of soy when it comes to breast cancer. This goes for breast cancer patients who are currently undergoing treatment. And according to MD Anderson Cancer Center, this even applies to people with estrogen-positive types of breast cancer or the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

So where did the myths about the dangers of soy start? For that, we need to quickly address some of the issues with early studies done in animals.

Issues with Animal Models for Isoflavone and Cancer Research

In the 1990s, we were learning a lot about the mechanisms and functions of phytoestrogens and isoflavones. During that time, a series of animal studies were published that showed isoflavones could stimulate the growth of existing breast tumors in mice (read more HERE and HERE).

Of the three isoflavones found in soybeans (genistein, daidzein, and glycitein), it was believed that genistein stimulates tumor growth.

These animal studies fueled a lot of fear and mistrust around eating soy. But we can’t take data from animal studies and apply it directly to humans. Both mice and rats metabolize isoflavones very differently than humans as well as each other. This applies to many other areas of nutrition research, but it’s especially relevant when talking about soy and cancer.

The mice used in these studies were athymic, ovariectomized mice. Athymic mice are a special type of lab rodent that do not have a normal thymus gland. They’re often used in cancer research because the lack of a normal thymus gland prevents them from rejecting tumor cells. This would alter the outcomes of the research for obvious reasons. It’s a means of trying to control for a significant variable.

Ovariectomized mice have their ovaries surgically removed. They’re used in estrogen research because if they kept their ovaries, the researchers would have to contend with a female mouse’s own hormone production.

So although using this type of animal model can control for certain important variables, it also means we can’t rely on them to determine how the effects would show up in humans. In fact, when studies were repeated in different animals models that were more similar to humans (meaning, intact ovaries and thymus glands) there was a complete loss of the tumor-stimulatory effect of genistein.

And as I shared above, the data from human studies does not show the same findings as these previous studies using mice.

If you or someone you care about is wondering about soy and cancer, I hope you’ll hang onto this post to share and spread the word! Eating soy is not linked to an increased risk of breast cancer.

But what about other types of cancer? I’ll cover that in the next section, so keep reading to learn more.

Soy Isoflavones and Testosterone

Alright, we’ve covered soy isoflavones and estrogen. Now we’re turning our focus to another important sex hormone: testosterone.

This section is going to be short and somewhat boring. Because based on what we currently know, eating soy has no impact on testosterone levels.

This is based on a research analysis that found that eating 40-70 mg of soy isoflavones a day (from food sources or soy supplements) had no impact on hormones or semen quality. To give some context, an entire block of tofu has about 100 mg of isoflavones. In some isolated cases, extremely high intakes have led to issues (which you can read more about here). But safe to say, if you’re a man worried about soy undermining your masculinity, don’t be.

And when it comes to fertility, there’s still no cause for concern. Soy isoflavones have no effect on sperm concentration or quality.

But it’s only fair that if we debunked dangers of soy for breast cancer, we should also look at prostate cancer and other types of cancer.

Facts About Soy and Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is unfortunately very common. According to estimates from the National Cancer Institute, there were 288,300 new cases or prostate cancer diagnosed in 2023. That’s slightly more than lung cancer (238,340). And only slightly lower than new breast cancer diagnoses (297,790 for women, 2,800 for men).

But similar to what we saw with breast cancer, the incidence and deaths from prostate cancer look different depending on where you are in the world. In Asian countries, the rate is very low compared to Western countries. Some Asian population studies showed that higher soy consumption is associated with as much as a 50% reduction in prostate cancer risk. This is yet another indication that eating a moderate amount of soy foods throughout your life can be beneficial. However, we need more longitudinal studies to say this with certainty.

We don’t have quite as much research in this area as we do for breast cancer. As a result, there are limitations to how we can interpret the findings. But here’s what we know at this point:

- Several intervention studies have shown that is-flavone exposure slows the rise of PSA (prostate specific antigen) levels. PSA is used as a screening tool and to monitor for prostate cancer recurrence.

- However, this is in contrast to other long-term trials that showed no effects for preventing recurrence or progression of prostate cancer.

- And as noted above, eating soy nor being exposed to isoflavones affects testosterone levels in men. This means there is another possible mechanism of action to explain the proposed protective effects.

We need more research to fully understand exactly how soy may be beneficial for prostate cancer patients. But for now, it does not appear to cause harm. Soy intake is associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer, according to a 2018 meta-analysis of 30 studies. Three previously published meta-analyses concluded the same thing.

Soy and Other Types of Cancer

The majority of the research on soy and cancer focuses on breast cancer and prostate cancer. We aren’t as clear on the role of soy for other types of cancer.

Here are a few key findings to add some context:

- Colorectal cancer (CRC) is another commonly diagnosed cancer. Higher intake of soy foods was associated with a reduced risk of CRC in some people (premenopausal women with a BMI <23) but was associated with higher risk of CRC in others (postmenopausal women and men with BMI ≥27.5). In Asian populations, soy consumption is associated with a reduced risk of CRC. But take this statement with a grain of salt because there are limited studies to analyze. Many of the dietary records were self-reported food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) and could be confounded by recall bias.

- For gastrointestinal cancer, a meta-analysis of 22 prospective studies found no association between soy consumption and GI cancer incidence or mortality. The authors noted “a higher intake of soy product is associated with the decreased risk of overall GI cancer and gastric cancer, but not colorectal cancer. This protective effect was observed in females but not in males.”

- For thyroid cancer, neither soy foods nor isoflavones increase TSH levels in people with normal-functioning thyroids. Epidemiological data from Japanese women found that soy intake was unrelated to thyroid cancer risk. And a case-control study in a U.S. population found an inverse relationship between is-flavone intake and risk of thyroid cancer. In other words, as with other cancers, it seems that eating soy foods does not increase risk and may have a small protective effect.

- An emerging research focus is the role of soy foods and isoflavones for skin health. When it comes to skin cancer and melanoma, the research is extremely limited. However, it’s proposed that soy could reduce risk. We only have animal studies at this point, which can’t be translated directly to humans. Although some findings were intriguing, we can’t form conclusions or make recommendations specific to skin cancer quite yet.

While the majority of currently available evidence points to no risk or possible benefit for soy and risk of certain cancers, there is one exception to note.

Although the incidence of bladder cancer is relatively low in Asia, two prospective studies in a Chinese population suggested a possible increased risk. However, no relationship was found in a meta-analysis that included these two studies. It’s probably no surprise to hear this, but we need more research to fully understand this relationship.

The Bottom Line

If you skipped ahead to this section, you missed a lot of info! But I don’t blame you. If you’re facing a cancer diagnosis you might want the facts without all the fluff.

Based on what we know so far, there’s no reason not to include a moderate amount of soy foods in your diet. The one exception: a soy allergy, in which case you should absolutely stay away to avoid an allergic reaction.

But we have a solid foundation of research supporting the benefits of soy. In almost all cases, there is a positive benefit or slightly protective effect. Or, no association meaning it doesn’t help but it doesn’t hurt. In reality, most of us here in America aren’t eating much soy to begin with. So adding a couple of servings to your regular, balanced diet won’t have any downsides.

Despite these facts about soy and cancer, many people are still afraid to include it. This fear is based on shaky interpretations from animal studies and misinformation.

It’s ultimately your decision about whether you want to eat soy foods or not. I think you should also consider factors like your budget, lifestyle, and taste preferences.

I hope this breakdown on soy and cancers helps debunk the “dangers of soy”. As a registered dietitian who advocates for fearlessly nourishing meals, my goal is to help you make informed choices about what and how you eat.

Thanks for reading!