Welcome to the Intuitive Eating FAQ Series. This is where I answer some of the most frequently asked questions about Intuitive Eating and a non-diet approach. Read more to learn more about orthorexia and what it can look like.

QUESTION: I’ve seen the term, but what is “orthorexia”? And is it considered a type of eating disorder?

ANSWER: There’s a lot of overlap with orthorexia and dieting, disordered eating, and eating disorders. While the term “orthorexia” has not been clinically recognized as an eating disorder and is not included in the DSM-5, it’s something I notice in clients quite often. Before we get into it further, here’s an important disclosure: this post is intended to provide information only. It is not intended to diagnose, manage, or treat any medical conditions and we will always recommend consulting with your healthcare team for individualized recommendations or advice.

To start, what exactly is orthorexia? It’s defined as the preoccupation with the quality of food and a pathological fixation with healthy eating. When we use those clinical-sounding words to describe it, it can certainly sound like a disorder or something to be ashamed about. But it’s very common so if you’re struggling with this, you’re not alone.

Obsessive thoughts around food can show up as eating only “pure” or “clean” or “natural” foods and actively avoiding anything considered “unhealthy”. Does this sound familiar based on any popular diets from the last decade or so? This attempt to “eat clean” is, ironically, not exactly health-promoting when it comes at the cost of your mental and emotional well-being. Estimates for the prevalence of orthorexia range from 6.9% to 75.2% [1] depending on various evaluation tools and population demographics.

When we think of eating disorders (EDs) and disordered eating, we often think of thin, white, female bodies. That’s what we’ve historically been shown and the result is an inaccurate stereotype. Yes, people in thin, white, female bodies can and do struggle with EDs and disordered eating. But EDs don’t discriminate – the latest studies report an equal prevalence of orthorexia among men and women. [1] Orthorexia, dieting, and disordered eating are also very common across the gender, age, ability, race, and ethnicity spectrums.

Many people who have dieted in the past display signs of orthorexia, and research suggests that orthorexia may come before or be the residual of an eating disorder [2]. That doesn’t mean everyone who tries a diet will go on to develop orthorexia, but there is a link between orthorexic tendencies or a diagnosable ED and past attempts at dieting or weight cycling.

Orthorexic tendencies are also most often associated with perfectionism, which is connected with the development and perpetuation of eating disorders. Therefore, it is believed perfectionism could be a potential risk factor for developing orthorexia, along with the preoccupation with weight and appearance [2]

How does orthorexia show up?

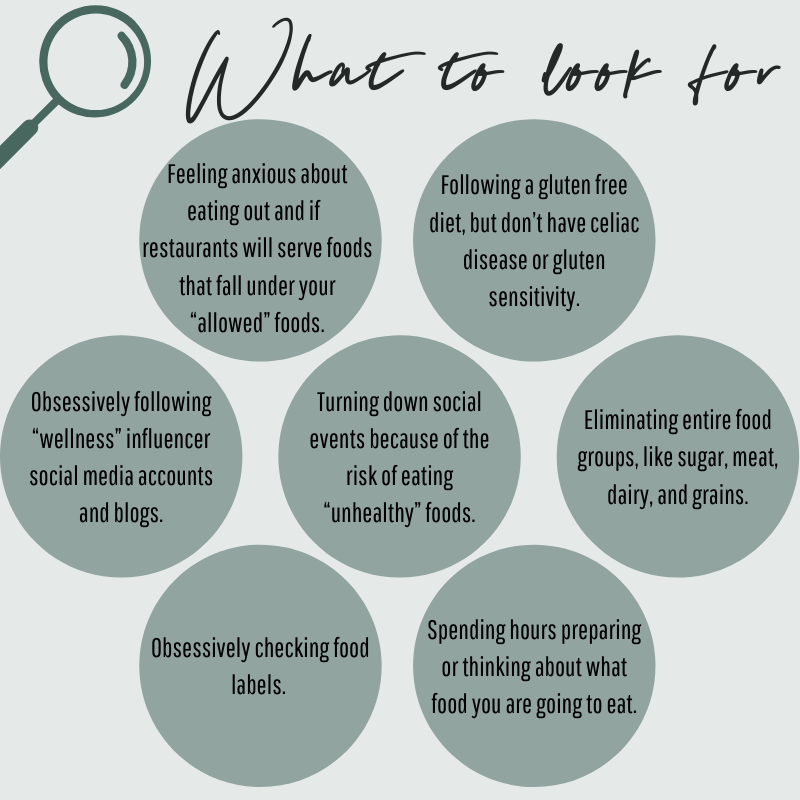

The overlap between orthorexia, dieting, and eating disorders can be blurry, but it might show up in the form of food rules and the need for tight, rigid control. While other forms of restrictive eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia are fixated on the quantity of food, orthorexia is focused on the quality. This can look like cutting out specific food groups, such as dairy, sugar, meat, and only buying organic and non-GMO foods. Here are some examples of warning signs:

I want to reassure you that nothing on this list offers proof that you’re a “failure” or a bad person. One of the signatures of a dieting or disordered eating mindset is lots of shame, guilt, or regret over our actions with food and eating. If you’re noticing one or more of these things coming up for you, there’s an opportunity to get curious about your relationship with food (without casting harsh judgment or criticism on yourself). One of the tools I highly recommend is Way, a non-diet app I helped develop. Click HERE for more resources!

How is orthorexia diagnosed?

If there’s so much overlap with orthorexia and dieting, disordered eating, and eating disordered, how can orthorexia be diagnosed and treated?

This is what makes diagnosis challenging. A person who chooses to eat nutritious foods, exercise, and build health-promoting habits may come across as healthy or disciplined to others. However, there could be other underlying pathological characteristics going on, which makes it difficult to distinguish between deciding dietary intake and the pathological behavior that can develop when both have the goal of achieving a healthier diet.

While orthorexia has not been clinically recognized as an eating disorder and is not included in the DSM-5, the following diagnostic criteria have been proposed:

- obsessive behaviors and preoccupation with healthy nutrition that includes rigidly following a restrictive “healthy” diet (that the individual believes to be healthy and pure) combined with a strict avoidance of foods believed to be unhealthy [3]

- deviation from dietary rules can result in extreme emotional distress with feelings of guilt, shame, and/or anxiety [3]

- physical impairments as a result of nutritional deficiencies that can lead to significant weight loss, malnutrition, and/or physical health complications [3]

- psychosocial impairments in social, vocational, and/or academic functioning that may result from the other-diagnostic criteria [3]

Street Smart Nutrition Tip: Even though registered dietitians can work to treat eating disorders and support people in eating disorder recovery, they cannot diagnose them. A diagnosis is made by a physician or mental health professional. Be wary of anyone else who tries to declare a diagnosis. They are likely unqualified and may cause more harm than good with attempts to treat or manage symptoms!

The commonly used measures for diagnosing orthorexia primarily focus on the first criterion involving obsessive behaviors and preoccupation with “healthy” eating. However, none have included a substantial amount of items that assess a person’s emotional distress from violations to these self-imposed dietary rules or the physical harm that may develop as a result of nutritional deficiencies [3]. Therefore, experts believe that identifying and diagnosing orthorexia should encompass a wider range of diagnostic tools given the various impacts orthorexia can have on one’s health and wellbeing.

What are the consequences of Orthorexia?

Behaviors in orthorexia patients can differ greatly from person to person, since the idea or definitions of what is considered “pure” or “healthy” is decided on an individual level. Therefore, the patterns of restriction will vary and show up in different ways. However, we know that rigid diets can lead to a lack of variety when it comes to nutrition and there is little deviation in the types of foods consumed. From this, long-term consequences can include malnutrition and malnourishment.

Outside of the nutrition implications, there are also impacts on quality of life and mental health that are important to highlight. The extreme rigidity of orthorexia can lead to isolation or increased anxiety and depression. Sharing meals is an important way people come together and form social bonds. By frequently avoiding social gatherings or events due to the anxiety that comes with navigating eating within these self-imposed rules, it can lead to isolation or loss of relationships.

If you feel like your behaviors around food are starting to mimic these dieting behaviors, and you have created food rules or you have started to lose sight of what is “normal” when it comes to eating, it’s important to start getting curious with yourself and ask how dieting may be showing up in your life.

Here are a few questions you can start with:

- If you estimated how much time you spend thinking about food every day, how much is it? 10%? 50%? More than 80%?

- As a follow up, do you think you’d feel happier or healthier if you thought about food less or could focus on other things?

- What benefits do you feel like you’re getting from continuing to live or eat this way?

- What concerns or fears do you have about living or eating a different way?

- Why do you feel the need to label yourself according to a particular diet or lifestyle? Do you feel like your way of eating has become part of who you are or part of your identity?

- Which food rules are no longer serving you? Are there any you feel ready to start letting go of?

It’s been said before but it needs to be said again: this post is intended for information only. It is not intended to diagnose, manage, or treat any medical conditions and we will always recommend consulting with your healthcare team for individualized recommendations or advice.

References:

- Niedzielski, A., & Kaźmierczak-Wojtaś, N. (2021). Prevalence of Orthorexia Nervosa and Its Diagnostic Tools-A Literature Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(10), 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105488

- Barnes, M. A., & Caltabiano, M. L. (2017). The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eating and weight disorders : EWD, 22(1), 177–184. https://doi-org/10.1007/s40519-016-0280-x

- Oberle, C. D., De Nadai, A. S., & Madrid, A. L. (2021). Orthorexia Nervosa Inventory (ONI): development and validation of a new measure of orthorexic symptomatology. Eating and weight disorders : EWD, 26(2), 609–622. https://doi-org/10.1007/s40519-020-00896-6

Special thanks and author credit to Kristen Nicolai for her support with the planning and execution of this post.